Author William A. Haviland

A conversation with Bill Haviland, author of Indian History on Deer Isle

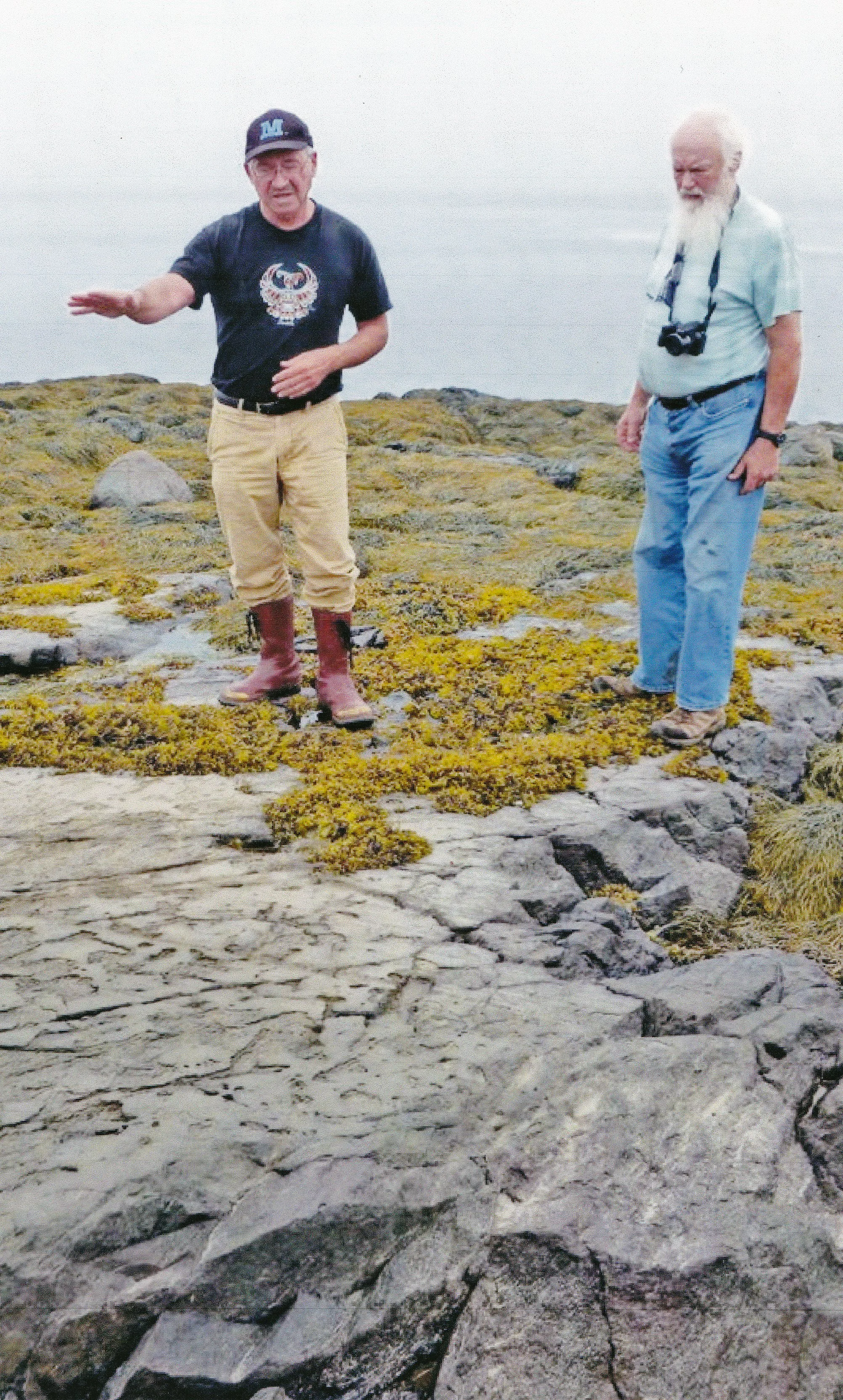

Bill Haviland, right, with Passamaquoddy Donald Soctomah. Courtesy of Abbe Museum, Bar Harbor, Maine

Ask the Author

My interest in local Indians goes back to my childhood. This was the era of “cowboys and Indians” and the Indians fascinated me more than the cowboys. Summer boat trips to the islands around Deer Isle opened my eyes to the many coastal shell heaps left by the Indians, and to cap it all off there were visits to the Mitchell family’s “Indian Camp” in Sunset. In college, I discovered the work of anthropologist Frank Speck and others, and I wrote many a term paper on aspects of Penobscot culture. In my senior year, I did an honors paper on the archaeology of Maine, which I expanded into a Master’s thesis two years later. At that point, however, I got diverted to Maya archaeology in Guatemala.

You use the term “Indian” rather than the term “Native American.” Why?

As an Abenaki friend put it, “It’s silly. Anyone born in the Americas is a native American.” In fact, the American Indian Movement (AIM) has just reaffirmed their name. And we still have the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Museum of the American Indian. Here in Maine, we still have Indian Island, and Indian Township.

To those who argue that “Indian” is a misnomer, so too is native American, for the reason given by my Abenaki friend. To be sure, Indian people prefer to be called by their ethnic label: Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Malecite, Mi’kmaq or Wabanaki as a blanket term for all Indians within the state. Personally, I like the Canadian blanket term: First Nations. Not only is it not misleading, but it emphasizes their inherent sovereignty. Meanwhile, however, I continue to use the blanket term American Indian, as long as activists in AIM do so.

At the University of Vermont your interest in local Indians was renewed. What was that like, and what was the result?

When I began my career at the university (in 1965), I naturally started asking around about archaeological sites. The usual reply I got was “Indians never lived in Vermont.” The source of this opinion came from a widely-read book called Vermont Tradition by Dorothy Canfield Fisher. It made no sense at all to me, and I soon encountered individuals who for years had been picking up stone tools and ancient pottery exposed in freshly plowed fields. So I began writing the occasional article in between my work to create a department of anthropology at the university, publishing the results of my research on the ancient Maya, and producing a textbook in anthropology that went on to become a best seller. To make a long story short, I saw the creation of a state archaeological society. I also developed a relationship with Abenakis living in northwestern Vermont and collaborated with a colleague on a book about Vermont Indians (both ancient and modern) and spent three days in Vermont District Court as an expert witness for the Abenakis in a case over fishing rights (we won).

What rekindled your interest in local Indians following your retirement from the University of Vermont in 1999?

When I retired, my wife and I returned to live in Deer Isle full time, and I began writing unsolicited “guest columns” for the local newspaper, Island Ad-Vantages. I had always read books on Maine history and was concerned that, if Indians were even mentioned, they generally disappeared when the state was settled by colonists. Moreover, when Indians were mentioned, the amount of misinformation was appalling. So I thought it was time to restore Indians to the state’s history. I have tried to do this through talks and boat trips around Deer Isle, as well as through numerous articles in the media. When I moved here, I had it in mind to write a book on local Indians. The present book is now my fifth, plus the numerous articles I have written for the Ad-Vantages and other publications. In the fall of 2022, the publisher commissioned a series of articles, which are at the core of this book. I have added other columns I have written, plus sections from some of my books no longer in print.

What are you working on now?

I have just completed a series of five memoirs recounting my experiences in the jungles of Guatemala and my research at the ancient Maya city of Tikal, now on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Four of the memoirs have been published in The Codex, a publication of the Precolumbian Society at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. I plan to continue my interest in local history, both Indian and non-Indian.